Quercus (Oak) Notes

Campus oaks

More than the redwood on its seal, Stanford’s tree scene is set by its native oaks, dominated by the coast live oak, the most numerous tree on campus – the oak that establishes the deep, rich green against which every other green is compared. Valley and blue oak follow in frequency, the latter most abundant in the foothills, though indigenous giants can be found on central campus – one stands before Dinkelspiel Auditorium – and in the Arboretum as well.

Oaks hybridize, almost always within their own section (see below). Jolon oak, a named hybrid of valley and blue oak, is undercounted and hence understudied in the area; inventories rarely flag it explicitly. Our understanding of species evolves, too: at Jasper Ridge, Shreve oak and relictual Palmer oak were thought to be other species – though for different reasons; see their entries. Shrub oak species and the California black oak also grow at Jasper Ridge, though not the majestic goldcup oak that becomes common in the mountains just beyond.

History

Frederick Law Olmsted specified vast numbers of coast live and interior live oaks for propagation for Stanford’s grounds. They are “live” oaks because they’re evergreen: our mild climate and plentiful sun throughout winter allow them to make food all year long. He made no mention of the deciduous valley and blue oak. Gardener Thomas Douglas did locally collect and sow acorns of valley and coast live oak; he sowed California black and goldcup oak as well. But his work diaries made no mention of blue oak either, despite grand specimens then (and still) standing in the Arboretum, steps from his nursery.

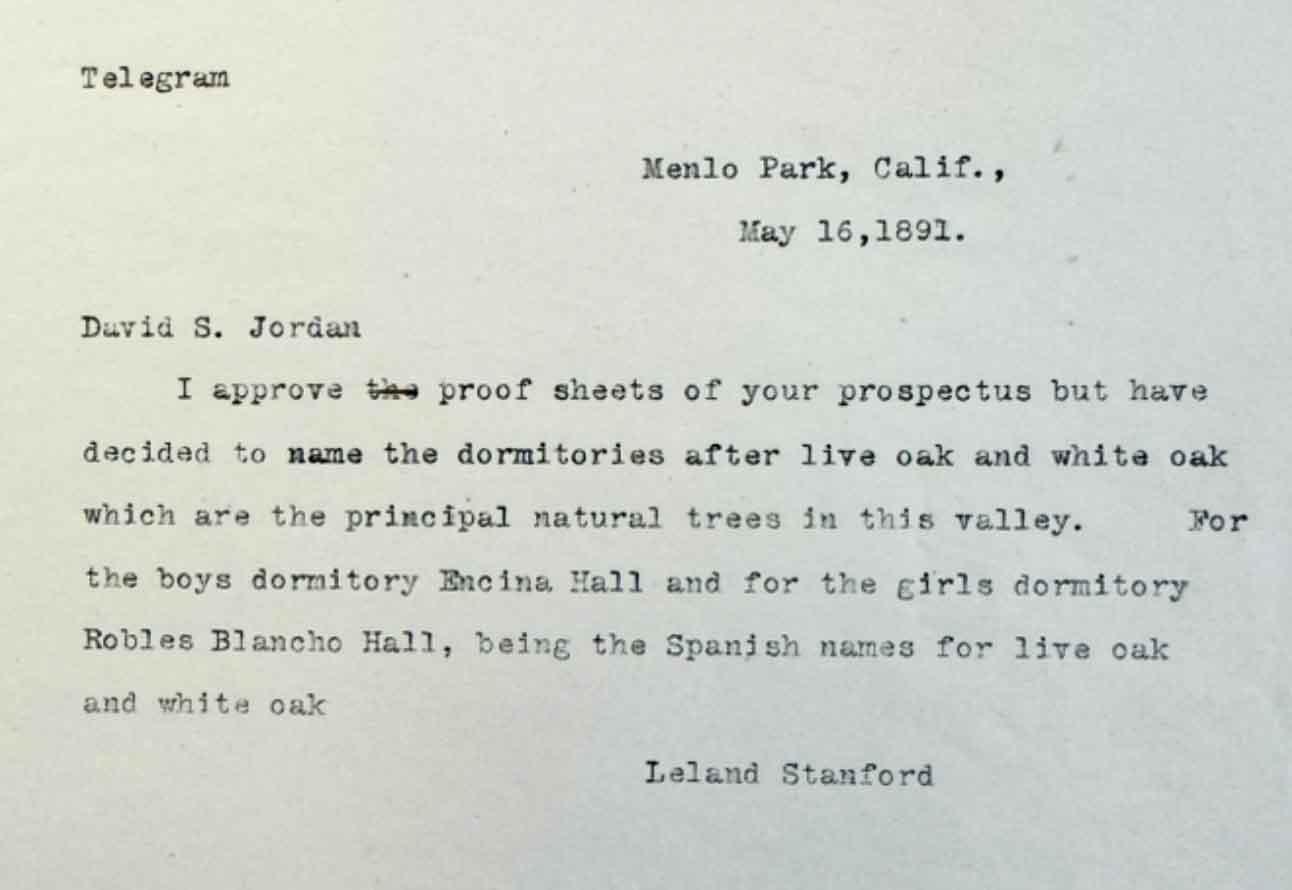

Leland Stanford wished, as far as possible, that no mature oak be sacrificed to campus development. He directed that the first dormitories be named after the Spanish monikers for coast live oak and valley oak. In a telegram to David Starr Jordan dated May 16, 1891, he wrote:

I approve the proof sheets of your prospectus but have decided to name the dormitories after live oak and white oak which are the principal natural trees of this valley. For the boys dormitory Encina Hall and for the girls dormitory Robles Blancho [sic] Hall, being the Spanish names for the live oak and the white oak.

Tenants and troubles

Native oaks are central to local biodiversity discussions, hosting as they do a plethora of minute organisms fundamental to the food web, their benefits amplified by the sheer prevalence and size of these trees. Noting which creatures participate in the complex ecology of oaks – or any plant – sharpens our sense of their ecological value, though the line between providing habitat and suffering from it is not always clear.

California oak moth and tussock moth caterpillars chew coast live oak leaves; in outbreak years, the larvae often descend on silk threads.

The native oak root or honey fungus (Armillaria mellea and kin) occurs naturally in the roots of coast live oak and many other oaks. It fruits as honey-colored edible mushrooms at the trunk base. Problems are exacerbated with horticultural conditions such as summer irrigation near the root crown – all but unavoidable in lawn conditions, though keeping turf and watering well away from trunks helps.

Sudden oak death, caused by the fungus-like organism Phytophthora ramorum, has killed millions of tanoaks and many oaks along the California–Oregon coast since the mid-1990s. Coast live oak and California black oak are the most susceptible oaks; other natives such as redwood, toyon, madrone, and bay laurel usually show foliar or twig infections only. Bay laurel, especially, can pass on the infection to adjacent oaks and tanoaks. Jasper Ridge has been monitoring for this disease; thus far, our oaks have been spared.

Gall-spotting is an under-appreciated pastime: scan our oaks’ leaves for an array of sometimes colorful growths of fantastical shapes, with pleasingly apt names: striped volcano, spined turban, red cone, pink bowtie. These are formed of plant tissue in response to wasps that lay eggs within; the structures shelter the developing larvae. Other invading organisms such as fungi and bacteria can also induce galls.

Mistletoes are hemiparasitic plants that usually photosynthesize but tap the tree’s water and nutrients, usually not damaging the host. Clumps are sometimes seen on our deciduous oaks such as valley, as well as on scarlet and water oak. About a dozen large clumps were carefully removed from the sizeable water oak near Bing Concert Hall in 2024.

Burls – large, knobby swellings on trunks or branches – arise from proliferating (often dormant) bud tissue, typically triggered by some kind of stress but also fungal and other infection; their intricate grain is sometimes prized. A coast live oak between Kingscote Gardens’ east entrance and the Humanities Center bears an immense, rounded burl bulging on either side of the trunk. Pepper tree trunks are often heavily burled.

Acorns

For most native Californians, acorns were a daily staple. Among the local Puichon, nuts of valley, black, and coast live oak were ground and then leached in water to remove the bitter tannins; a large rock with food grinding holes on top can be seen at Jasper Ridge.

Other preparations were known. Among the Shasta, acorns were buried in swampy ground for a year, then roasted and eaten whole; another method let shelled acorns mold in a basket before burial in clean river sand until they blackened and were deemed ready. Across cultures, from California to the Mediterranean, acorns have long been prepared in various ways, and are still valued in regional traditions most famously as seasonal feed for pigs in the oak woodlands of Spain and Portugal.

Oak planting at Stanford

David Schrom, founder of the local group Magic, observed in the 1970s that few younger native oaks were in evidence and that most mature trees appeared to be of similar age. In response, Magic has led extensive plantings at Stanford since the 1980s, in collaboration with campus grounds management – a decades-long experiment in establishing native oaks. Student volunteers sow acorns in the Dish, guard them with protective tubes against deer and rodents, and return to water until the seedlings are established. Often two species are sown in the same hole to test vigor; the weaker one is not always culled, the resulting twin stems making for curious pairings in the field. By 2000, more than 2000 trees had been established, mostly by direct seeding.

On campus proper, Magic trial various non-local oaks at various peripheral sites, for example near Palo Road opposite Hoover Pavilion and along Galvez Street near El Camino Real. Many acorns came from the Shields Oak Grove, the renowned quercetum at UC Davis. In such a mixed collection, wind pollination makes provenance uncertain; unsurprisingly, many seedlings turned out hybrid. Engelmann oak has been a notable success and is now used in choice campus sites; Canby oak is increasingly seen as well.

Our native California black oak has achieved at best moderate success on campus; the grove in Lathrop Park is the most established. Shreve, goldcup, and shrub oaks have seen little experimentation in recent decades, nor has tanoak. Blue oak’s story is treated in its own entry.

A four-year survey of native oak species in Palo Alto concluded in 2002 that there were about 13,000 individuals: coast live constituting 84%, valley 15%, and blue plus black less than 1%. A volunteer mapping effort begun in 2017, based on citizen entries, currently shows coast live at 78%, valley at 19%, and blue and black each at about 2%.

The oaks native to California are QQ. agrifolia, chrysolepis, douglasii, durata, engelmannii, garryana, kelloggii, lobata, palmeri, parvula, sadleriana, tomentella, and wislizeni, as well as several hybrid and shrub oak species; nine or so are described here.

In addition, Stanford has several U.S. oaks from

outside California, chief among them

QQ. coccinea,

macrocarpa,

palustris,

rubra, and

virginiana.

Campus oaks from other countries include

QQ. cerris,

ilex,

robur, and

suber.

Oak classification

Quercus subgenus Quercus

New World, high-latitude clade. Mainly in Americas, some Eurasia & north Africa.

section Lobatae: red oaks

- native to North, Central and South America.

- Styles long, acorns mature in 18 months (rarely 8 months – agrifolia), very bitter, inside of acorn shell woolly

- Cupule fused with peduncle forming a connective piece, which along with the cupule is covered with thin membraneous triangular scales with broad angled tips

- Leaves: teeth with bristle extensions, or just bristles without teeth

- QQ. agrifolia, wislizeni, kelloggii, ×ganderi (kelloggii × agrifolia), ×morehus (kelloggii × wislizeni); nigra, palustris, canbyi, shumardii, hypoleucoides, rubra, etc.

- Southwest USA and northwest Mexico

- Styles short, acorns mature in 18 months, very bitter, inside of acorn shell woolly

- Only 5: QQ. chrysolepis, palmeri, tomentella, cedrosensis, vacciniifolia

- Only 2: QQ. sadleriana (N Calif, S Oregon), pontica (Turkey/Georgia)

- QQ. virginiana, fusiformis, etc.

- white oaks from Europe, Asia, north Africa, Central and North America

- Styles short; acorns mature in 6 months, sweet or slightly bitter, inside of acorn shell hairless

- Cupule scales have keels & often covered with bumps (tuberculate)

- No spines or bristles on teeth (but many exceptions, e.g. berberidifolia, dumosa, durata)

- QQ. lobata, garryana, douglasii, engelmannii, oblongifolia, berberidifolia, dumosa, durata, ×jolonensis (lobata × douglasii); macrocarpa, alba, robur, rugosa, etc.

Quercus subgenus Cerris

Old World, mid-latitude clade. Mainly in Eurasia, some N Africa.

sect. Cyclobalanopsis: ring-cupped oaks

- E & SE tropical Asia

- Distinctive cupules bearing concrescent rings of scales

- Styles medium-long; acorns mature in 12–24 months, appearing hairy on the inside. Evergreen leaves, with bristle-like extensions on the teeth

- QQ. ilex, rotundifolia, coccifera/calliprinos, etc.

- Europe, north Africa and Asia.

- Acorn cup scales elongated with recurved tips; styles long; acorns mature in 18 months, very bitter, inside of acorn shell hairless or slightly hairy.

- QQ. suber, cerris, castaneifolia, ithaburensis, trojana, etc.

Name derivation: Quercus – classical Latin name for the oak, possibly derived from the Celtic quer, fine; and cuez, tree [from California Plant Names].

- Main References for New Tree Entries.

- Bold, E. K. 1962. Early Uses of California Plants. Berkeley: UC Press, 11–12. (Re. processing acorns by burial.)

- Denk, T., G. W. Grimm, P. S. Manos, M. Deng, and A. L. Hipp. 2017. “An Updated Infrageneric Classification of the Oaks: Review of Previous Taxonomic Schemes and Synthesis of Evolutionary Patterns.”.

- Jepson Flora Project (eds.). 2025. Jepson eFlora.

- Magic. 2019. “Oak Regeneration on Stanford University Lands: Diverse Oaks for Landscape Resilience.” Document hosted by Stanford Planning & Design.

- Muffly, David. 2024. “Surveying Experimental and Historical Oaks at Stanford.” Document hosted by Stanford Planning & Design.

- Pavlik, Bruce M., Pamela C. Muick, Sharon G. Johnson, and Marjorie Popper. 1991. Oaks of California. 4th printing, with revisions, January 2000. Los Olivos, CA: Cachuma Press. (Re. acorn consumption.)

- Stanford, Leland. 1891. Telegram to David Starr Jordon on dormitory names. May 16. SC 125, Box 1, Folder 3. Stanford University Special Collections & Archives.

About this Entry: Authored Sep 2025 by Sairus Patel.