Quercus coccinea

scarlet oak

scarlet oak

This tree is famed among oaks for its ruby autumn foliage – coccinea means scarlet – but sometimes retains patches of withered leaves through winter. It is often mistaken for pin oak, even by tree people, but may be distinguished by its larger acorns, ½–1 inch high and nearly as wide, with a turban-shaped cap that encloses a third to half the nut; fine concentric grooves or stippling can be seen at the tip of the nut. Pin oak bears noticeably smaller acorns with flatter, saucer-shaped caps. Both have 3–6 inch leaves with deep, bristle-tipped lobes, but scarlet’s sinuses are C-shaped, pin’s U-shaped. On the leaf underside, the tufts of fuzz where the lobe veins join the midrib are much less pronounced in scarlet oak than in pin.

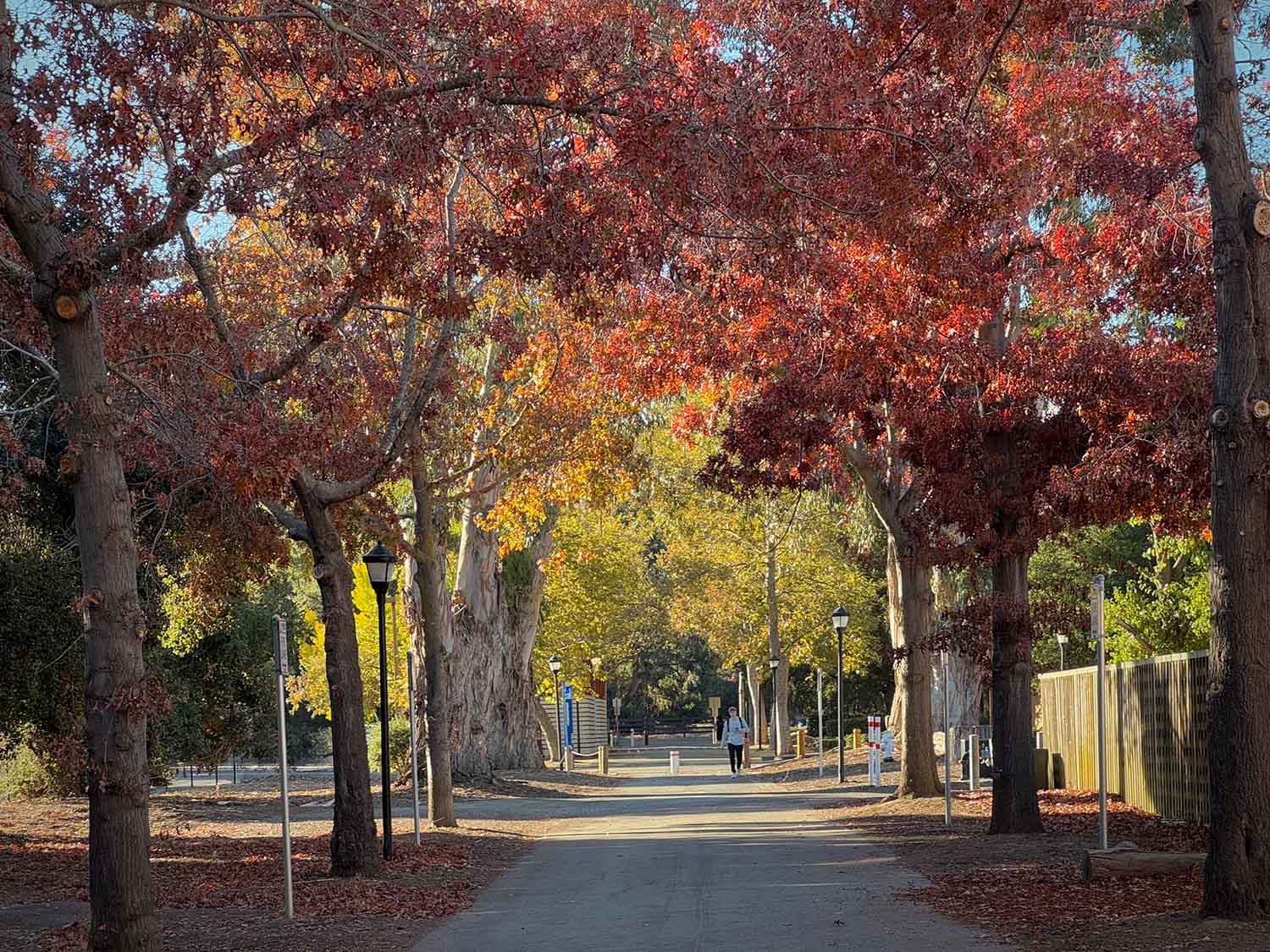

Governor’s Avenue South from Elliott Program Center toward Campus Drive is lined with scarlet oaks, some decked with clumps of mistletoe; once thought to be pin, their acorns and foliage confirm scarlet. More can be seen around the bend, at Murray and Yost Houses on Governor’s Avenue proper. Two youngsters grew for six years just west of the Stanford Wall sculpture in the east ear of the Oval (map pin), removed in 2024. A handsome Q. coccinea stands at 1610 Portola Avenue in Palo Alto.

Gallery

About this Entry: Authored Aug 2025 by Sairus Patel.