Sequoia sempervirens

coast redwood

coast redwood

Ascend our foothills and look to the Bay, and you will see Stanford stretched out before you, separated from the water by what looks like a swath of forest, coniferous spires rising through the haze. Visitors are at first puzzled, and then marvel that the buildings of Palo Alto have been entirely swallowed up by the trees from this viewpoint and even from atop Hoover Tower on campus itself. Coast redwood accounts for almost all of this upper-canopy urban forest. Then turn around and look westwards to the green slopes and peaks of the Santa Cruz Mountains to see redwoods in their native haunts.

Close relatives of the redwood once flourished across the Northern Hemisphere, but the group has now retreated to redwood’s current habitat along the Coast Ranges from southwestern Oregon to Big Sur in California. There it is bathed in the fog that supplies it the plentiful water it needs, especially in our rainless summer months: the fog catches in the crown, the moisture not only dripping to the soil below but directly absorbed by leaves and even bark.

The coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) is often confused with its massive cousin, the giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum), which is also known as Sierra redwood and has similarly thick reddish bark. The California legislature designated the “California redwood” as the state tree in 1937 – but which one? Well, both species, the attorney general clarified later on, one might imagine sheepishly. (Nevada is the only other US state with two official trees – the single-leaf pinyon and the famously long-lived bristlecone pine.) The two redwoods are actually quite easy to tell apart at any time of year: coast redwood’s short, flat needles are arranged in two-dimensional sprays; giant sequoia’s triangular, awl-like scaly leaves are pressed closely around the branchlet. Turn over a spray of coast redwood and see faint white lines of stomata under each leaf. The two-ranked sprays look very much like a pinnately compound leaf; even arboreally inclined sorts, when asked to point out a single leaf, rarely select a single small needle, which is the correct answer.

The sprays look very similar to the deciduous ones of Taxodium, and this was indeed the genus first given it, along with species sempervirens (Latin for ever-green or ever-flourishing). Later, its genus was changed to Sequoia by an Austrian botanist and linguist who was likely aware of Sequoyah (circa 1770–1843), born in Cherokee country in Georgia, who invented a syllabic Cherokee alphabet that enabled tribal literacy. The connection to Sequoyah was not made explicit, however, and there is a competing claim that Sequoia derives from the Latin word for sequence. In any case, avoid using just the word Sequoia to refer to coast redwood in conversation, since many might think you mean the giant sequoia, unless you can somehow pronounce the capitalization and italics correctly. Using an unqualified “redwood” is common and acceptable; rarely is the Sierra redwood so called these days.

Sequoia sempervirens can live for over 1000 years, breaching 2200 years in some records. Unlike many long-lived trees, it grows rapidly, achieving much of its height within its first hundred years. It is a race of giants, easily growing to 200 feet tall in the right conditions. Dozens of measured examples in the wild exceed 360 feet. The tallest known, Hyperion, named for a Titan god, was discovered in 2006 and reaches over 380 feet – the tallest tree in the world. (The name is cognate with our words hyper, over, and uber.) The next three contenders are within 9 feet; measurements need to be precise. Climbing up, when allowed, and dropping a tape measure is the gold standard.

Save the Redwoods League and Humboldt State University research shows marked increases in growth rates of old-growth redwoods in the latter half of the 20th century, possibly due to increased carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere, a longer growing season, and, for some areas, increased access to sunlight due to decreasing fog. They also concluded that old-growth redwood forests sequester more carbon above ground than any other forest on Earth.

Logging of redwoods in the area of San Francisquito Creek began soon after 1777, the founding year of both Mission Santa Clara and the pueblo (town) of San José. The 1849 Gold Rush swiftly transformed San Francisco into a booming city, creating substantial demand for lumber and redwood shingles. The virgin and very accessible groves at Jasper Ridge must have been among the first to go; stumps still remain along San Francisquito Creek there, sprouting vegetatively from their peripheries into second-growth fairy rings in three major groves on the south banks.

Redwoods were planted in preparation for the university’s opening in 1891. Their popularity hasn’t waned. Since the turn of this century, they have been planted at the Clark Center (Bio-X), mixed in with deodar cedars; on either side of the renovated Old Chemistry building; and in the medians of extended sections of Campus Drive near the Clark Center and from Wilbur Field to Manzanita Field, their lower branches sweeping to the ground when space permits and trimmed up near intersections for traffic visibility. The substantial redwoods near Salvatierra Walk and behind the Law School once stood in the gardens of early faculty homes long since replaced by academic buildings. Stanford’s tallest redwood, around 115 feet, is in a small grove between the Faculty Club and Kingscote Gardens.

Two groups flank the south end of Canfield Court including a single bluish-leaved cultivar, ‘Filoli’, on the eastern group. The ortet (original) of ‘Filoli’ was found in the Santa Cruz Mountains near Filoli estate, Woodside (and not on Stanford land, as some rumors have had it), and subsequently cloned and propagated by the Saratoga Horticultural Foundation. Another clone of the cultivar stands at Filoli itself, at the edge of the open area north of the swimming pool; it had been a gift to the estate’s owner, Mrs. Lurline Roth, in the late 1960s or early 1970s and first planted on the lawn terrace. The original is said to have perished in a fire.

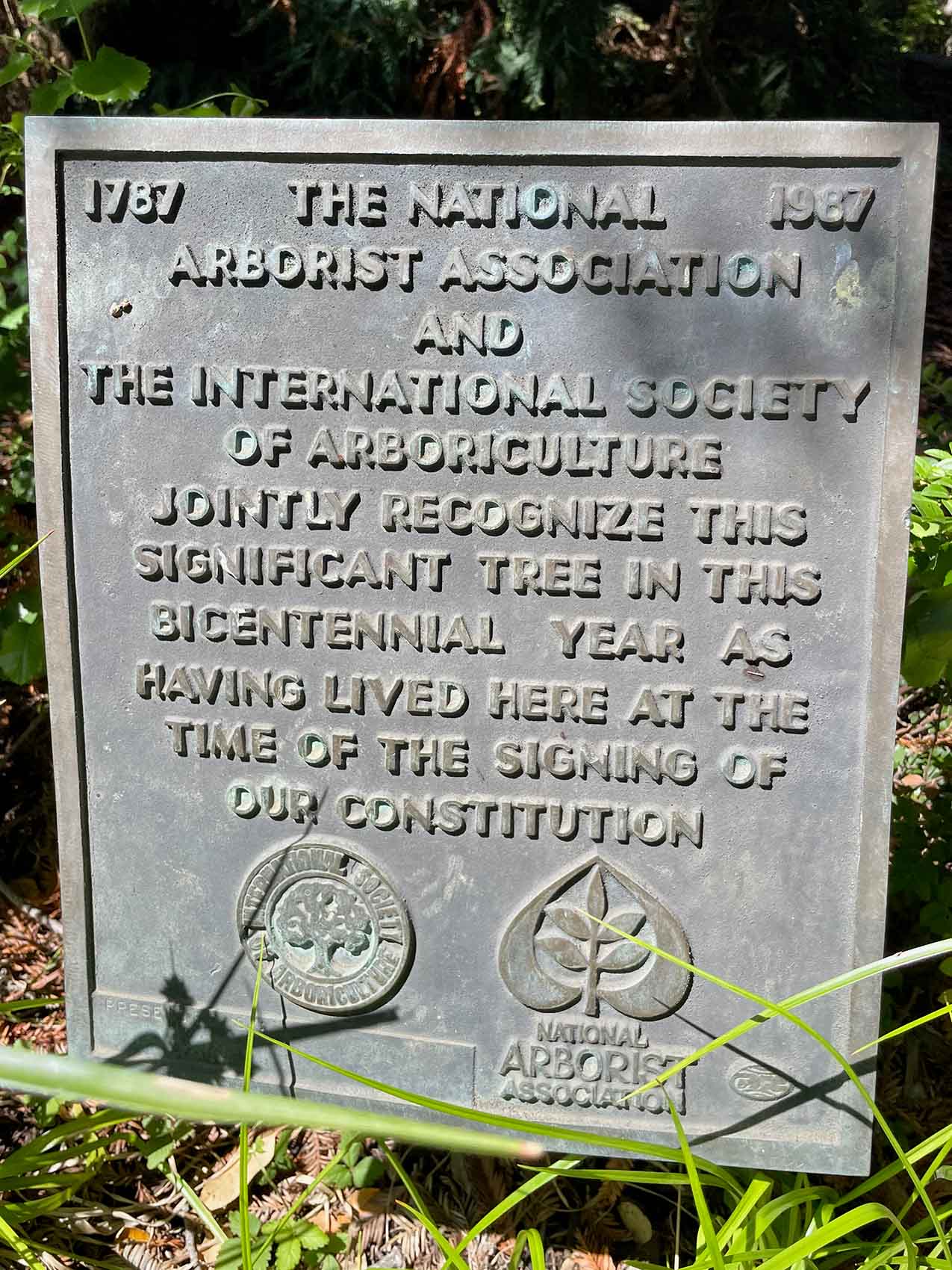

A group of five redwoods, the largest with a 15-foot girth, is off Jane Stanford Way east of Computing And Data Science, with a plaque reading as follows:

Stanford Palos Altos

These redwoods were planted in 1915 by Stanford botany professor and pioneer American plant physiologist George J. Peirce, faculty member from 1897 to 1933. in accordance with Professor Peirce’s intention, the university named these natural monuments “Stanford Palos Altos.” They symbolize Stanford’s strength, independence, and enduring quality.

El Palo Alto, for which the city of Palo Alto is named and which appears on Stanford’s seal, stands beside San Francisquito Creek in Palo Alto.

A specimen

probably planted in 1924 at 1509 Portola Avenue, Palo Alto, measured 114 feet

in 1995. The backyard coast redwood at 3759 La Donna Street, an official Palo Alto

heritage tree, measured 125 feet tall with a diameter of 64 inches in 1999.

El Palo Alto

The revered Palo Alto redwood stands in our eponymous neighboring city in a special eponymous park just north of where its eponymous avenue crosses the railway tracks. It anchored a corner of Rancho San Francisquito, the first land acquisition made by the Stanfords on the Peninsula, in 1876, lending its name to the Stanfords’ farm, the Palo Alto Stock Farm, and later to the city of Palo Alto, officially incorporated in 1894.

Its likeness – sometimes scraggly, sometimes fuller – appears on multiple versions of the University seal; an early Board of Trustees seal (1908) shows it flanked by the words Semper Virens. The mascot of the Incomparable Leland Stanford Junior University Marching Band, conceived in 1975, has been thought to represent El Palo Alto but has in recent years resembled a willow, maple, and even tulip tree.

This historically isolated redwood, growing on the south bank of the San Francisquito Creek, can be seen in old photographs and drawings, mysteriously distant from its native range in the Santa Cruz Mountains. Perhaps seeds floated down the creek or were planted, and then sustained by the seasonal waters of the creek. Once twin-trunked, the second trunk came down in 1875 or thereabouts, mostly likely in a fierce storm. The City’s core sample testing suggests it germinated in the year 940, making it 1085 years old in 2025. Today, it stands 110 feet tall, though in 1951 it measured 134 feet. Its diameter is 7.5 feet.

The first Europeans in the Bay Area arrived somewhat accidentally in 1769. A Spanish exploring party led by Gaspar de Portolá traveled north from San Diego in search of Monterey Bay. That bay turned out not to match the description they had, so they pressed on northwards. Along the way, they became the first Europeans to observe coast redwoods and record a name for them. Father Juan Crespí, the expedition’s diarist, called them palo colorado (red tree). When the party reached what is now San Francisquito Creek, they forded it near present-day west campus and camped there. No mention has been found of them noticing our landmark tree.

Five years later, another Spanish expedition scouting for a place to establish a mission dedicated to Saint Francis camped at the same location, planted a cross at the ford to mark the desired mission site, and named the creek Arroyo de San Francis. A remarkably tall redwood downstream of the ford was noted. The mission ended up being established in present-day San Francisco instead, and the creek, renamed Arroyo de San Francisquito, became a boundary between the territories of Mission San Francisco de Asís and Mission Santa Clara.

El Palo Alto Gallery

Name derivation: See text above.

- Main References for New Tree Entries.

- Watt, Jeff (October 6, 2024). “El Palo Alto: A Fresh Look at the Mysteries of the Tall Tree,” talk given at the Palo Alto Historical Society.

About this Entry: Authored Mar 2025 by Sairus Patel.