Eucalyptus mannifera

red-spotted gum

red-spotted gum

Sunset magazine popularized the red-spotted gum by growing a splendid specimen in front of its headquarters in Menlo Park (Willow Road at Middlefield Road), with a clean white bole and carefully maintained crown. Alas, it is now gone. When Frenchman’s Hill was developed for faculty residences in 1969, a network of footpaths was provided that would allow walking or biking to school while avoiding the roads. Some of the paths would be shaded by the highly esteemed red-spotted gums. This planting of 170 trees stretched from Amherst Street to Raimundo Way. An experimental eucalypt planting of 1958 that previously screened Ryan Laboratory from Stanford Avenue included one red-spotted gum on Raimundo Way that stood as an elder citizen until 2002, but the rest of that early planting, including E. lehmannii, E. maidenii, E. platypus, disappeared when Ryan Laboratory was replaced by housing. A striking feature of the new trees is the fresh white surface of the bark revealed yearly after peeling. You can rub the white powder off with your finger and decorate your face, just as the Australian aborigines did for a corroboree.

A complaint about leaves falling into a swimming pool and an insurance problem over fence damage, compounded by a concern that a branch might fall on a schoolchild, caused Faculty-Staff Housing to call a town meeting in July 1985 at which replacement of the whole planting by Chinese pistache was advocated. In similar circumstances, city officials receive legal advice that they may be liable if they ignore a danger of which they have been previously warned, for example if a branch should later fall on a child. The administrative response followed in adjacent cities is to obtain independent outside advice from a professional tree inspector, to follow the recommendation for remedial pruning or removal of trees judged to be dangerous by regular arboricultural standards, and to keep records. This procedure shields administrators against damage suits, provided they can show a record of compliance with professional advice.

In the event, the outcome was that residents wanting a particular tree removed should obtain the acquiescence of neighbors. About one in seven of the trees went; some of the replacement pistaches died but others, such as those on the path leaving Raimundo Way just west of Vernier Place, have flourished. Meanwhile, no branch has fallen on a child, nor indeed has any eucalypt dropped a branch on any person on campus. (Damage to parked cars and fences by falling trees has occasionally occurred, mainly due to oaks. In 2002, Prince Charles bemoaned politically correct interference that led to the felling of chestnut trees in England because of fears that falling chestnuts would cause injuries.) From a cost-of-removal standpoint, E. maculosa is not in the class of large eucalypts. The Midpeninsula Open Space District removed 19 tall eucalypts at Rancho San Antonio Open Space Preserve at a cost of $1900 each (San Jose Mercury News, August 5, 1992). (See Ulmus minor for the $1500 cost of removing an elm in 1985.) On the other hand, after the freeze of 1978, when the temperature at Stanford did not rise above freezing for three days, 100 E. globulus on Governor’s Avenue were harvested by a Santa Rosa logging company at no cost to Stanford (Palo Alto Times, May 30, 1978).

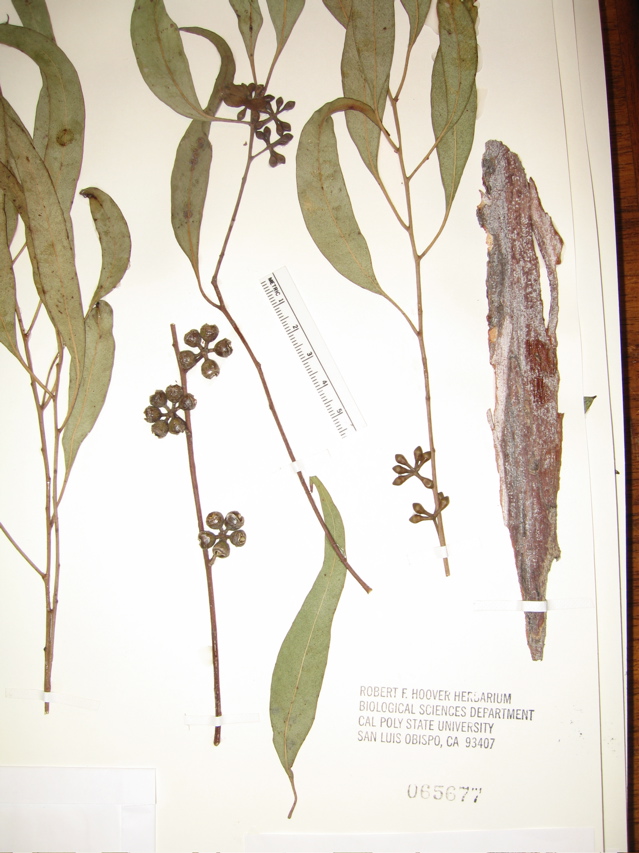

Illustrations: branchlet | capsules (valves slightly exserted) | peeling bark.

Related material: Eucalyptus checklist.

About this Entry: The main text of this entry is from the E. maculosa entry in the book Trees of Stanford and Environs, by Ronald Bracewell, published 2005.