Eucalyptus camaldulensis

river red gum

river red gum

The most well-known eucalypt in Australia, river red gum is the beloved subject of much art in that country. Its shapely crowns and massive twisted boles, often reflected in waterways, can be seen in countless paintings and photographs of tranquil pastoral scenes.

The most widely distributed eucalypt on the continent, it grows mainly along riverbanks and floodplains throughout the mainland states except for the wonderfully named Nullarbor Plain and certain other areas. Its seven identified subspecies occupy mostly distinct areas of its range and differ mainly in the details of their flower buds and fruit. One subspecies dominates the river systems of temperate southeastern Australia, another is widespread across the interior arid zone, and another to the tropical north. Much of California’s stock, with its largely pendulous branches and scraggly form, has surprised visiting Australians. Since it is a highly variable species, seed provenance counts, but it may be that the trees will grow to grander dimensions simply by getting more water. “Tolerance” to drought doesn’t always indicate much more than survival.

The ruddy heartwood, highly resistant to termites, gives the “red” in its common name. The species name, bestowed in 1832 by Friedrich Dehnhardt (1787–1870), refers to Hortus Camaldulensis, the Neapolitan garden which he oversaw and in which he grew this and a handful of other eucalypt species. Details in his luminous watercolors helped confirm, in 2019, that the kind of eucalypt he had described was indeed what we now know as E. camaldulensis, after that had been thrown into doubt by a study in 2008. The garden was that of the Count of Camaldoli, whose title referred to the order of monks founded a thousand years ago in Camaldoli, in the verdant Tuscan Apennines. (The New Camaldoli hermitage was established in the Santa Lucia Mountains of Big Sur, California, in 1958. There, you can gaze down at the vast Pacific out of the picture window in your guest bedroom while contemplating the Brief Rule of Romuald, the founder of the order, framed on the wall.)

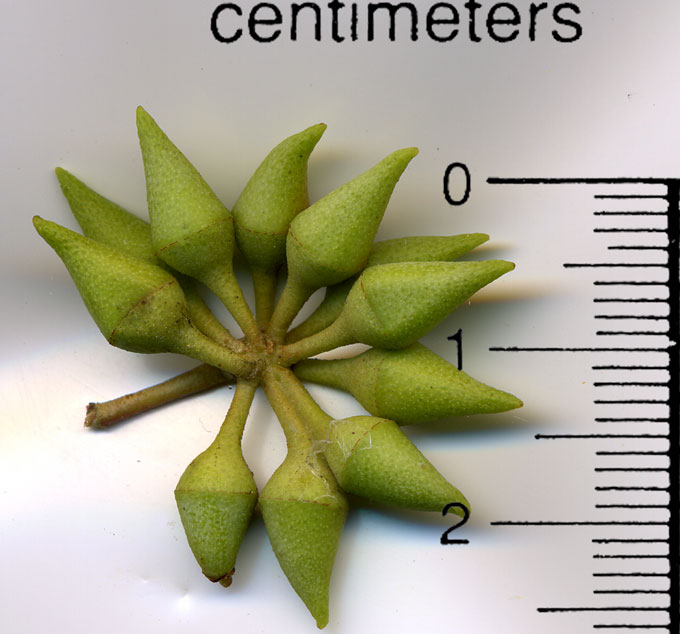

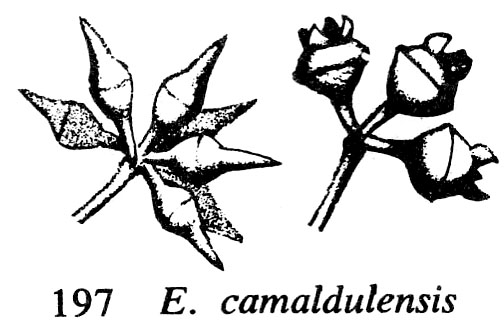

Many campus specimens have smooth, peeling bark in large patches of cream, pale gray, and brown-gray. Some have persistent, rougher bark at the base of the trunk. Stalked buds in groups of 7 (though sometimes as many as 11) can always be found in the litter below, and have beaked or conical opercula. The small, papery, outer operculum is perched over the inner one, and is shed early, leaving a scar at its former base. The growing flowers push off the inner operculum. The valves in the center of the mature fruit protrude out fiercely.

In the center of campus, find a trio of river red gum to the right of the coffee stand in front of Green Library’s East Wing, two at the northeast corner of the East Wing, and one on Panama Mall overlooking Terman Fountain. All are mixed in among red ironbark. Red gums were planted as an avenue on Searsville Road, where some still remain, along with large blue gums. Other old specimens can be seen across Galvez Street from the football stadium among a plantation of mostly blue gum. A dozen are planted in the parking lot west of Lagunita Court, and various specimens are mixed in with other eucalypts along Campus Drive behind Knight Management Center. River red gum, like blue gum, has fallen out of favor for new plantings on campus. Many have been prone to psyllids, sap-sucking insects that form tiny sugary tents called lerps on the leaves.

Related material: Eucalyptus checklist.

- Main References for New Tree Entries.

- Del Guacchio, E., Bean, A. R., Sibilio, G., De Luca, A., De Castro, O., & Caputo, P. (2019). “Wandering among Dehnhardt’s gums: The cold case of Eucalyptus camaldulensis (Myrtaceae) and other nomenclatural notes on Eucalyptus.” Taxon, 68(2), 379–390.

About this Entry: Authored Jan 2025 by Sairus Patel.