Notholithocarpus densiflorus

tanbark oak

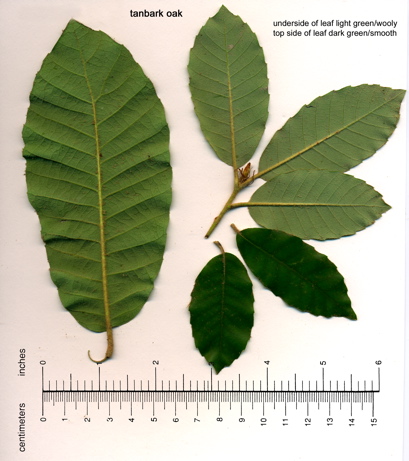

tanbark oak

Native to the coast ranges including the area immediately adjacent to campus, the handsome tanbark oak has been widely utilized in California for its lumber and for its bark, used in tanning hides. Many trees are rich sources of tannins, colored astringent substances that contribute flavor to red wines and tea, temporarily stain the sidewalk below olive trees, and are a traditional ingredient in ink.

Tannin was a bulk industrial product for converting skins to leather. Before 1970, Australia was supplied with tannin by plantations of Australian acacias in South Africa, which has hundreds of species of its own, a quaint fact that illustrates the market zeal that had gone into testing the world’s flora for a profitable crop. Owing to the replacement of leather soles by rubbery plastic, to the reduced need for horse harness, and to chemical substitutes, the tannin industry has shrunk. However, since cattle are still being raised and skinned for food worldwide, leather remains a cheap commodity. You can make tannin yourself by soaking acacia bark in water. If skins of furred animals are not available, try making leather from fish skins.

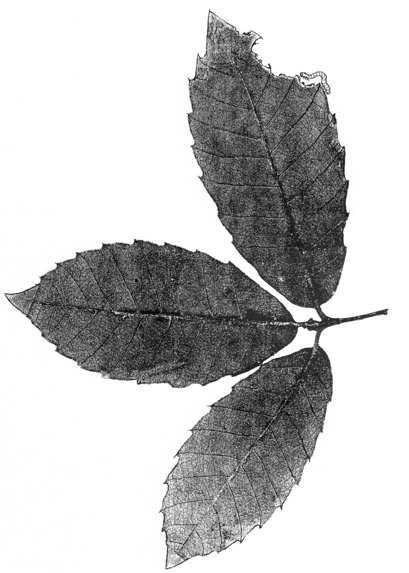

The largish plump acorns of tanbark oak are set only shallowly in their cups, which are characteristically woolly, reminiscent of the prickly burr of a chestnut. In fact, the tanbark oak is no longer classified as an oak by botanists but has a genus name of its own to recognize its status between the oak and the chestnut. It differs from the chestnut in having an acorn in a cup and from the oak in having erect terminal catkins containing male flowers in threes rather than pendulous strings of single male flowers. The leaves are leathery, toothed, up to 4 inches or so long, and have pale tan felt underneath that can be rubbed into balls with the finger.

Attractive specimens grow in the lower parking level at 725 Welch Rd. Curiously, campus’s only other tanoaks are just a couple of blocks away, also on Welch Road, opposite 1000. Examples behind the stage in Frost Amphitheater were once numerous; they may have left a remnant.

Illustrations: Jasper Ridge photo archive.

About this Entry: The main text of this entry is from the book Trees of Stanford and Environs, by Ronald Bracewell, published 2005. Campus locations added (Jul 2024, SP).